INVISIBLE FORCES AT WORK

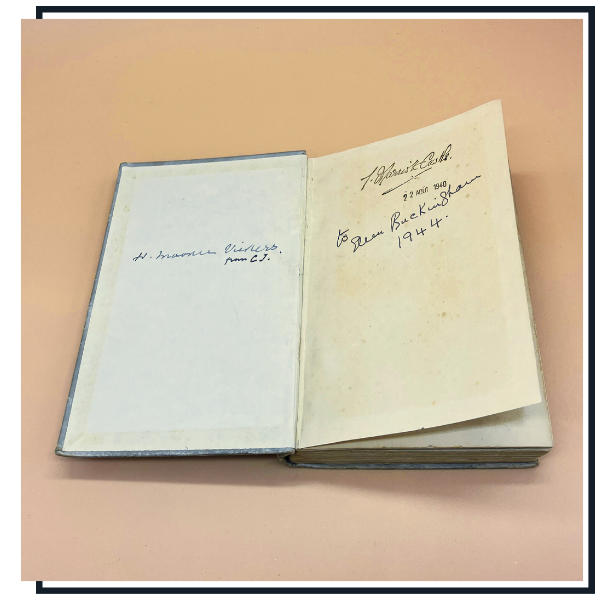

The Invisible Influence – Alexander Cannon

Alexander Cannon’s The Invisible Influence (1933) is a book written by a man who cannot decide whether he is explaining the world or casually admitting that it already knows far more than we do. It is not really a manual of hypnotism, nor quite an occult memoir, nor even a philosophy book, though it insists on being all three. Instead, it is a record of impressions – Cannon’s word, and a revealing one – gathered from yogis, hypnotists, doctors, mystics, patients, radio waves, snakes, ghosts, crowds, drugs, colours, music, and whatever else happened to wander into his consulting room or line of sight.

Cannon begins from a premise that feels oddly contemporary: people are not passive robots. They receive, filter, resist, distort, and retransmit suggestions constantly. Hypnosis, for Cannon, is not a parlour trick but an exaggerated version of something happening all the time. Speech is silver, silence is golden, and suggestion leaks through both. Telepathy is not a miracle but a discipline. Message control matters. Those who bark orders rarely influence anyone for long.

Throughout the book, Cannon returns to the idea that invisible forces are already operating socially and politically, whether we acknowledge them or not. Crowds become hysterical. Nations fall into shared beliefs. Winston Churchill’s voice on the radio produces what Cannon treats as a shared mental atmosphere – a small world suddenly tuned to the same frequency. Long before anyone called it a “national asset”, Cannon assumes that telepathic rapport, morale, and suggestion are being exploited by states whether they understand them or not.

His fascination with yogis and fakirs is less about mysticism than systems. He is suspicious of charlatans, noting how difficult it is to distinguish genuine altered states from mimicry, drugs, or theatrical enthusiasm. Cannabis appears as a crude way of faking trance. Animal magnetism is dismissed as a washed-out metaphor. Astrology is dragged in, examined, and quietly contradicted. Auras are entertained but never allowed to settle comfortably. Cannon is at his most convincing when he admits he cannot be bothered to control minds, only to observe how easily minds coordinate themselves without permission.

One of the book’s most striking undercurrents is ethical. Cannon repeatedly gestures toward “higher spheres of human ethics”, worrying about what happens when influence outruns responsibility. Hypnotism is powerful. Telepathy, if real, is more so. Public hysteria is not an accident but a consequence of systems being hacked by greedy or ignorant actors who do not understand what they are handling. The ignorant masses appear often, but Cannon is just as wary of overconfident experts who believe technique alone makes them immune.

There are moments of near-modern insight. Cannon suggests that hypnotic scales tell us more about the hypnotist’s enthusiasm than the subject’s depth. Children, he notes, are extraordinarily perceptive and copy generational coping mechanisms with alarming accuracy. Systems must be flexible or they collapse. Minds meet. Worlds contradict one another. People represent entire universes, not magnets responding predictably to force.

And then there are the glorious digressions. A friend hypnotised by a snake. An evening of childish experiment. Astral projection clubs apparently over-subscribed even in the 1930s. Animals incapacitated by suggestion. Demons suggested politely away. Ghosts removed from books by wireless friendship. If Cannon sometimes sounds like Professor X without the wheelchair, he also sounds like someone aware that the joke may be on him.

The Invisible Influence ultimately reads like a book written through a glass, dimly. Cannon is not wrong so much as unfinished. His certainty frays into speculation, his speculation into anecdote, his anecdote into something that still feels uncomfortably familiar. The invisible forces he describes never quite become supernatural, nor do they settle into science. They remain impressions – and perhaps that is the point.