HOW DO YOU KNOW IF YOU’RE HALLUCINATING?

Toward a Theory of “Hypnotic” Behavior: Positive Visual and Auditory Hallucinations – Theodore Xenophon Barber

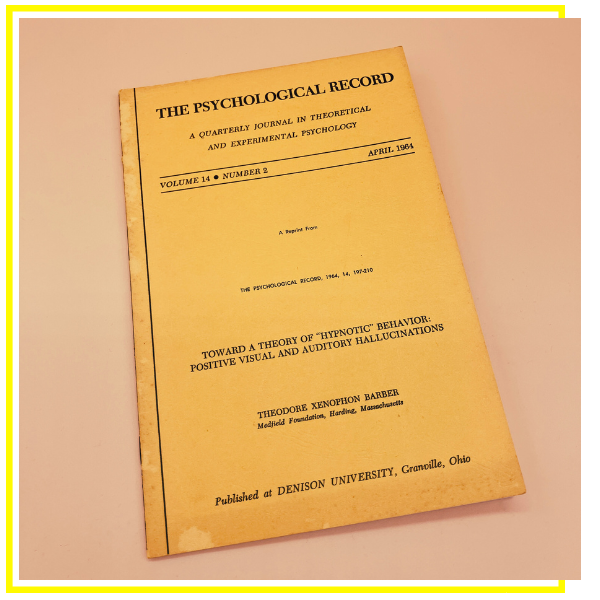

This is not strictly a book, because it is – strictly – a peer-reviewed paper, published in ‘The Psychological Record’, 1964, Volume 14, Number 2, on pages 197 to 210. But the form I have in my hands is a physical reprint. With a cover. And pages. And it cost me money. So, it’s kind of a book, even if it isn’t very long. It’s at least a pamphlet, and certainly more than a flyer. It’s just odd to come across such a professional reprint when the best you get today is a PDF. I kind of knew these existed, but I assumed they would have been photocopied in the department and stapled in the corner. This, on the other hand, implies a press, but no price tag, other than the one in pencil from a second-hand bookshop.

Regardless, if you’re going to choose a paper to reprint, why not choose one of Barber’s? He was revolutionary with his views on the hypnotic state, matched only by his ruthless pursuit of experimental data to test his assumptions. In this paper he reviews studies of hypnotic hallucinations, including some of his own. The main question posed is whether hypnotic hallucinations are perceived the same way as our usual perceptions; eg, do visual hallucinations look like real life?

The first test reported is one that exploits an auditory effect that inhibits speech. Basically, if you playback someone’s speech, slightly delayed, it makes it very hard to talk. But when the playback is hypnotically hallucinated, the effect doesn’t appear, making auditory hallucinations appear differently to reality, at least in this regard. A similar trick has been pulled with optical illusions whereby hallucinated overlays have failed to produce distortions in perceived images. Again, it appears that hallucinations aren’t the same as the real thing.

The next one reminded me of Barry Thain, who I used to chat with on an unofficial Derren Brown forum in the 2000s, and who spoke at the hypnotism conference, ‘ change | phenomena * ’, in 2012. He once told a story where he suggested that when a participant opened their eyes they would only see blackness, but that when he clapped his hands they would see normally again; and that when he did clap his hands, their pupils responded rapidly to the perception of incoming light. Barber reports that something similar was tested by Lundholm in 1932 but the supposed effect was not observed.

Then there are a handful of studies finding that people experienced hallucinated afterimages from staring at hallucinated images. The theory is that if someone stares at a real image for a period of time (30s, 2 minutes, who knows?), and then stares at a white sheet of paper, they will see an afterimage related to the image they were staring at. So if someone stares at a hallucinated image, and then at a white sheet of paper, do they see a hallucinated afterimage? Well, yes, and no.

Yes, they do see hallucinated afterimages. But no, they do not correlate with the colours that are recorded when people stare at real images. They do correlate, however, with the colours that textbooks often report for afterimages! Wait, what? They hallucinate afterimages from hallucinated images, but not based on their own actual experiences of afterimages from real life, but based on their perception of afterimages informed by widespread but incorrect textbooks? Which means that they aren’t “seeing” afterimages because they stared at a hallucinated image, but because the demand characteristics implied they would. Because if it was due to the image, then surely the hallucinated afterimage would follow the normal process of generation, resulting in the usual colours. But in these cases, the afterimages were generated using memories of information about afterimages, implying they were imaginary from the outset (as should be expected!).

With regards to whether a hypnotic induction and “trance” were required, well, it’s Barber, so of course not! People could hallucinate with task-motivating instructions just as easily as they could with an induction. And the big one, whether they felt real or not? Barber concludes “that it appears parsimonious, at the present time, to categorise the suggested hallucination under the general psychological rubric of imagination rather than perception”. And I think that kind of sums it up. All suggested hallucinations are imagined, and people can tell them apart from real life.